Fall 2015 Teaching

Reading over my students' final essays from "Introduction to Ancient and Early Modern Political Philosophy" (syllabus) yesterday, I'm thrilled to witness the birth of political theorizing. So many of them have taken up the skill of integrating arguments from the history of political thought into their own considerations of political questions. To reflect on freedom, one student examines eleutheria (the ancient Greek word commonly translated as "liberty") in Aristotle and then contrasts this with Republican liberty in Polybius and Cicero. To develop her own thoughts on dissent and politics, another student links the need for contestation in Machiavelli's political theory with Socrates' ceaseless questioning. Yet these students do not merely survey what others have said. Instead, they take up this thought and bring it into their own inquiries and arguments. They make Aristotle, Polybius, and Cicero their own internal interlocutors, partners in the dialogue they have with themselves. The history of political thought thus becomes a resources they can internalize and bring to bear on the challenges and questions they face today.

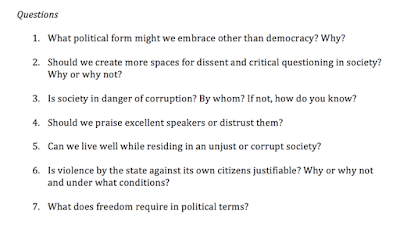

I want to think more about this process of integration, of internalizing and diversifying the dialogue of the self with the self. My framing of the course in terms of its "big questions" seemed to have helped here.

The questions connected to the students' lives insofar as they identified themselves as living in democracies (or wanting to) or prided themselves on tolerating dissent. I had a good feeling about this class from the first day, when our discussion of the desirability of democracy drew from students' experiences in India, Pakistan, Hong Kong, China, Vietnam, Russia, Brazil, Canada, and the United States. The stakes of defining democracy are unavoidable when considered from these multiple positions.

The times our discussions flagged came when the topics felt too distant from the students. I could have bridged these gaps more, but I didn't anticipate that the health of the soul, for instance, would not compel them. I feel this concern so viscerally, in such a chest-thumpingly embodied way, that I found students' complaints of the "abstractness" of Plato's Gorgias flummoxing. I read a passage aloud, in stentorian voice, to convince them but it failed to penetrate. I need to devise new ways of showing my students why what seems abstract might matter.

It was a political class. They loved Aristotle and Polybius and found Socrates annoying. Herodotus's Constitutional Debate became a frequent point of reference (to my delight) and Aristophanes' Clouds fell away. By "political" here I mean a concern for what Aristotle calls the arrangement of offices and duties. The students wanted to discover the best forms of living together. They wanted, for the most part, constructive political theorizing.

I write "the students" but I should add that their lack of homogeneity made the class even better. Some students defended monarchy as a form of rule. Others declared that Socrates deserved to die. I even read a final essay claiming, with Callicles (of Plato's Gorgias), that doing injustice is part of living well. Integrating the history of political thought introduces a new mode of disciplined thinking but it does not determine any particular political position. I just hope I can continue the conversation with these extraordinary young people.

[Addendum: I already posted a reflection on my other course this semester, "Arts of Freedom" (syllabus), on Serendip, the course management program we used. You can read that reflection here.]

I want to think more about this process of integration, of internalizing and diversifying the dialogue of the self with the self. My framing of the course in terms of its "big questions" seemed to have helped here.

The questions connected to the students' lives insofar as they identified themselves as living in democracies (or wanting to) or prided themselves on tolerating dissent. I had a good feeling about this class from the first day, when our discussion of the desirability of democracy drew from students' experiences in India, Pakistan, Hong Kong, China, Vietnam, Russia, Brazil, Canada, and the United States. The stakes of defining democracy are unavoidable when considered from these multiple positions.

The times our discussions flagged came when the topics felt too distant from the students. I could have bridged these gaps more, but I didn't anticipate that the health of the soul, for instance, would not compel them. I feel this concern so viscerally, in such a chest-thumpingly embodied way, that I found students' complaints of the "abstractness" of Plato's Gorgias flummoxing. I read a passage aloud, in stentorian voice, to convince them but it failed to penetrate. I need to devise new ways of showing my students why what seems abstract might matter.

It was a political class. They loved Aristotle and Polybius and found Socrates annoying. Herodotus's Constitutional Debate became a frequent point of reference (to my delight) and Aristophanes' Clouds fell away. By "political" here I mean a concern for what Aristotle calls the arrangement of offices and duties. The students wanted to discover the best forms of living together. They wanted, for the most part, constructive political theorizing.

I write "the students" but I should add that their lack of homogeneity made the class even better. Some students defended monarchy as a form of rule. Others declared that Socrates deserved to die. I even read a final essay claiming, with Callicles (of Plato's Gorgias), that doing injustice is part of living well. Integrating the history of political thought introduces a new mode of disciplined thinking but it does not determine any particular political position. I just hope I can continue the conversation with these extraordinary young people.

[Addendum: I already posted a reflection on my other course this semester, "Arts of Freedom" (syllabus), on Serendip, the course management program we used. You can read that reflection here.]